Financialization of Household Savings in India: Post-Pandemic Transformation | Episode 56

There will be more customers to serve in financial services, more capital to fund ventures, and more domestic firepower in capital markets.

India’s equity markets have shown remarkable resilience since the pandemic, buoyed not only by foreign investor interest but increasingly by domestic retail and high-net-worth (HNI) participation. This surge reflects a broader transformation in household savings behavior: a gradual but perceptible shift away from traditional physical assets (like gold and real estate) toward financial assets. While the trend was underway even before 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic marked an inflection point. Indian households, historically conservative with a preference for tangible assets, began embracing equities, mutual funds, and other financial instruments at an unprecedented pace.

The result is a post-pandemic financialization boom that has deepened India’s capital markets – yet the data shows there is still vast headroom for growth compared to global benchmarks.

In this episode, we delve into the narrative of how India’s household investment behavior is changing. Understanding this shift is crucial: it not only signals a larger pool of domestic capital but also points to new opportunities and responsibilities in India’s financial ecosystem.

From Physical Assets to Financial Assets: A Slow Turn, Then a Surge

For decades, Indian households have parked the bulk of their savings in physical assets – land, housing, and gold remain deeply ingrained in the cultural psyche as stores of value. Even today, these assets constitute more than half of total household wealth. However, a slow rebalancing has been underway. The share of household savings in financial assets (bank deposits, stocks, mutual funds, insurance, etc.) rose from ~39.5% in FY2005 to ~44.7% by FY2024. This change may appear modest over nearly two decades, but the significance lies in its acceleration during and after FY2021. The inflection point came around FY2020–21, coinciding with the Covid-19 outbreak, when the share of financial assets jumped by about 1% in a single year – a notable shift for an economy of India’s size.

What spurred this shift? Behavioral changes induced by the pandemic played a key role. With lockdowns and social distancing, many Indians – particularly the youth – turned to digital finance. Idle time at home, coupled with easy-to-use mobile investing apps and strong equity market performance after the initial Covid crash, drew a new wave of first-time investors. This period also saw bank deposit rates plunge (making traditional savings accounts less attractive) and a realization that financial assets could offer liquidity and returns that physical assets could not.

The result was a pandemic-era catalyst that nudged households to diversify their savings. Government data corroborates this trend: even though physical assets still dominate, financial asset accumulation post-2020 has picked up speed, signaling a behavioral shift in how Indians plan for their financial futures.

The Retail Investor Boom: Demat Accounts and Equity Participation

Perhaps the most striking evidence of financialization is the explosive growth in demat accounts – the gateway for equity investing. They have surged in number as millions of individuals joined the stock market for the first time in recent years- in FY2021 alone, the count of new accounts jumped 35% year-on-year, followed by an astonishing 63% growth in FY2022.

While one might have expected this to be a one-time spike, the momentum persisted even after the lockdowns. FY2023 and FY2024 saw ~28% and ~32% growth respectively, and FY2025 added another ~27%. This translates to tens of millions of new accounts each year. One can clearly see the outcome: as of FY2025, India had ~191 million demat accounts in total (a figure that was barely 40 million five years prior). In fact, calendar year 2024 alone saw 46 million demat accounts added, averaging 3.8 million new accounts per month – a testament to the retail investing frenzy.

Several factors underlie this boom- Mobile-first brokerage platforms lowered the barriers to entry for stock trading – opening a demat account can now be done with a few smartphone taps and an Aadhaar ID check. Zero-commission trading, simple user interfaces, and aggressive marketing by discount brokers (some of whom became household names) have made investing accessible to young, tech-savvy Indians.

Moreover, strong market rallies in 2020–2021 created success stories that further fueled retail enthusiasm (many new investors made quick gains in those early months, drawing in their peers). IPO fever also played a role: record IPO fundraising in 2024 – 62 companies raised over ₹64,000 crore that year – prompted many to open demat accounts just to get in on share allotments. It became common for families to open multiple accounts (in spouse’s or relatives’ names) to improve odds in popular IPOs.

Despite these huge numbers, India’s demat penetration is only ~14% of the population, well behind countries like China (~28% penetration), Japan (~30%), or the USA (~40%). And the active investor base is smaller – by September 2024, the National Stock Exchange (NSE) had about 47.9 million active clients (i.e., accounts that traded in the past year).

Parallel to this quantitative growth is a demographic shift in who is investing. The investor population is getting younger. According to NSE data, the median age of investors dropped from 38 years (in 2018) to about 32 years by 2024, and a similar drop is seen in average age. In FY2019, only ~22–23% of retail investors were under 30; by FY2025, nearly 40% of all individual investors are under 30. The share of senior citizens (60+ years) in the investor mix fell to just ~7%. This dramatic youth wave is attributable to the ease of mobile investing and the growing appetite of India’s digital-native generation to participate in equity markets.

College students and young professionals, who once might have shied away from stocks, are now a dominant force in new account openings – over half of new investors in FY2025 were under 30 by some accounts. This young cohort, armed with apps and information from social media/YouTube finance channels, has fundamentally changed the investor profile on Dalal Street.

Another encouraging development is the rising participation of women in the financial markets. Finance in India has long been male-dominated, but the gap is gradually narrowing. An SBI report noted that nearly one in four new demat accounts in recent years is opened by a woman, and women’s participation is increasing faster in many states than men’s. In the banking system too, women have been outpacing men: between FY2019–25, the number of bank accounts held by women grew ~9.3% CAGR (vs 3.5% for men), and their bank deposit values grew 13.6% CAGR (vs 7.4% for men).

The share of women in total individual bank accounts rose from 32.8% to 40.4% in that period. This empowerment is spilling into investing; women are increasingly joining the equity cult, aided by fintech platforms that have specifically begun targeting women investors as a segment. While men still form a majority of traders, the gap is closing – a positive sign for inclusivity in India’s financialization story.

The implications of the retail boom are profound for India’s capital markets. One immediate effect has been market resilience and stability.

In the past, Indian equities were heavily influenced by Foreign Portfolio Investor (FPI) flows – when FPIs sold, markets fell sharply. Now, with a strong cushion of domestic retail and institutional inflows, the markets are better buffered. For instance, throughout FY2022–2023, even as FPIs pulled money out during global tightening, domestic mutual funds (fed by retail SIPs) consistently bought equities, mitigating volatility.

Market experts note that the steady drip of new investors and capital “will help offset any potential outflows from overseas funds and keep volatility under check”, effectively reducing India’s reliance on foreign capital. SEBI’s research finds that household investments in equities jumped to ₹128 trillion in FY2024 from ₹84 trillion in FY2023 – a massive 52% rise in a single year – underscoring how much local money is powering the markets now.

This homegrown investor base is a key catalyst for India’s markets and is likely one reason Indian equities rebounded quickly from global sell-offs (such as those in 2022) and hit new highs by 2023–2024.

Mutual Fund Mania: SIPs and AUM Soar

If stock trading and demat accounts were one pillar of the financialization wave, the mutual fund revolution is the other.

Over the past decade – and especially post-2016 – mutual funds have firmly penetrated Indian households’ wallets, thanks in large part to the popularity of Systematic Investment Plans (SIPs) and relentless investor education campaigns (“Mutual Funds Sahi Hai” became a catchphrase). The numbers tell the story of a tremendous retail-led expansion in mutual funds:

Skyrocketing Folio Count: A mutual fund folio is essentially an investor account with an AMC. The total number of MF folios in India jumped from about 4.2 crore in FY2015 to 23.5 crore in FY2025, a 19% CAGR over ten years. Growth was especially sharp in recent years – FY2025 alone saw a 32% surge in folios (adding nearly 5.7 crore folios in one year). Notably, 92% of these folios belong to retail individuals (including high-net-worth individuals), not institutions. This indicates that tens of millions of ordinary Indians are now investing in mutual funds, many via SIPs of a few thousand rupees a month. Equity-oriented folios saw the fastest growth (33% YoY in FY25) as new investors predominantly choose equity funds, though hybrid and passive/index funds have also picked up.

The breadth of this participation – from big metros to small towns – underlines a cultural shift: mutual funds have become a mainstream investment avenue for the middle class.

SIP: The New Habit of Investing: The concept of investing a fixed sum every month in a mutual fund (SIP) has truly captured India’s imagination. SIPs instill discipline and long-term perspective, and they proved their worth during market volatility by keeping investors invested. Annual SIP contributions grew from ₹439 crore in FY2017 to ₹2,894 crore in FY2025 – that’s a 26.6% CAGR, and a more than 6-fold increase in 8 years. In FY2025 alone, Indians poured ₹2.89 trillion (2.89 lakh crore) into mutual funds through SIPs, up ~45% from the prior year despite a topsy-turvy market. In fact, May 2025 set a record with ₹26,688 crore of SIP inflows in a single month– the highest ever – propelling the industry’s total Assets Under Management (AUM) past the ₹70 trillion milestone.

By May 2025, over 8.56 crore SIP accounts were contributing monthly, an all-time high, and the trend of net new SIP registrations remains robust (nearly 60 lakh new SIPs were registered in May 2025 alone). This sticky money has provided a stable inflow base for mutual funds. Notably, even during market downturns, SIP cancellations have been relatively low; investors now exhibit maturity by continuing their SIPs through corrections, which has resulted in 51 consecutive months of positive equity MF net inflows as of mid-2025. The SIP culture marks a shift from opportunistic stock punting to systematic, long-term investing in India.

AUM Growth and Scale: The flourishing of mutual funds is perhaps best illustrated by the growth in assets under management. In March 2017, total MF AUM was ₹17.5 trillion; by March 2025 it had reached ₹65.7 trillion. That’s an 18% CAGR, significantly outpacing the broader stock market (the Nifty50 grew ~12.5% CAGR in the same period). The industry added over ₹12 trillion in AUM in just the 12 months of FY2025 (AUM was ₹53.4T in Mar’24, jumping to ₹65.7T Mar’25). Part of this is due to market appreciation, but a large part is net inflows: domestic mutual funds saw ₹8.15 trillion of net inflows in FY2025 across all categories. Equity funds led with ₹4.17T inflows as investors bought into dips, and even debt funds saw ₹1.38T inflows after several years of outflows (aided by declining interest rates).

The result is that India’s mutual fund industry now oversees over ₹72 trillion in assets (as of May 2025), equivalent to roughly $870–880 billion – a scale that makes it a significant player in capital markets (for perspective, ₹72T is about 28% of India’s current GDP).

Investor Behavior and Trends: The growth in AUM is not just a bull market story; it reflects changing investor behavior. Retail investors are increasingly adopting a portfolio approach – diversifying across equity, debt, and hybrid funds. The AMFI annual report notes that younger investors tend to prefer aggressive equity strategies, while older investors use hybrid funds for risk management, indicating a nuanced understanding of risk-return among the public. There’s also evidence of investors staying invested longer: the share of SIP assets held for over 5 years has risen, suggesting many are embracing long-term wealth creation and resisting the urge to redeem early.

Furthermore, mutual funds have spread beyond the big cities; a large portion of new folios and SIPs now originate from B30 (beyond top 30) cities, helped by digital access and distributor networks expanding. This bodes well for more even distribution of financialization across the country.

Despite this stellar progress, India’s mutual fund penetration remains low relative to global peers, which underscores the growth potential ahead. As of FY2025, India’s MF AUM is about ~18% of GDP, which lags far behind developed markets – the US is ~69%, the UK ~53%, Japan ~43% – and even trails China (~23%).

In other words, the Indian mutual fund industry could grow 3-4x and still only be on par with where many economies are today. This is a key reason why we remain bullish on the long-term runway: rising incomes, urbanisation, and awareness could feasibly push India’s AUM/GDP closer to, say, 30–40% over the next decade, unleashing tremendous flows into investments.

Visualizing this gap one can appreciate how under-invested Indian households are in mutual funds compared to their global counterparts – but also how much catch-up is possible as the financialization trend continues.

Additionally, within the mutual fund space, Systematic Investment Plans have made Indian fund flows much more resilient. Historically, Indian mutual fund flows were lumpy – retail investors would pour money in during bull runs and pull out at the first sign of trouble (often mistiming the market). That cyclicality has reduced thanks to SIPs acting as a “stabilizer.” For instance, even when equity funds saw a slight moderation in inflows to ₹19,000 crore in May 2025 (amid some market volatility), the month still marked the 51st straight month of positive inflows.

The steady SIP contribution (₹26k+ crore that month) cushioned the dip in lump-sum flows. Industry executives note this as evidence of maturing investor behavior, where individuals are no longer rushing for the exits during corrections but sticking to their plans. From a macro perspective, this maturation means the domestic money in Indian markets is becoming “sticky” and long-term, which is excellent for market stability and for providing reliable capital to businesses.

In summary, the mutual fund boom – characterized by a wider investor base, huge SIP inflows, and rapidly expanding AUM – complements the rise in direct stock ownership. Many new investors start with mutual funds via SIPs and some later graduate to direct stock trading or other instruments.

Together, these trends depict a decisive shift: Indian households are no longer shying away from financial assets. A phrase often quoted now is “Financial assets are the new gold”, capturing how the younger generation especially is prioritizing stocks and funds over the traditional rush to buy gold or property with every bit of savings.

The HNI Shift: Portfolio Management Services on the Rise

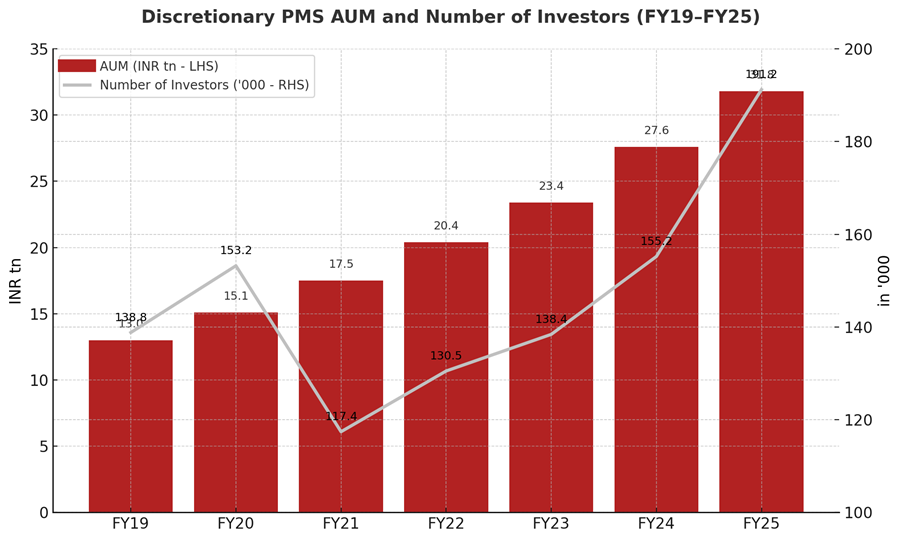

While retail investors drive the broad-based growth in financial markets, the wealthy segment of investors (HNIs) has also been changing its investment patterns – moving towards more sophisticated, professionally managed avenues. A standout trend here is the growth of discretionary Portfolio Management Services (PMS). These are bespoke investment accounts managed by professional portfolio managers, typically catering to HNI clients who invest sizable sums (regulations mandate a high minimum ticket size, e.g., ₹50 lakh, for PMS). Historically, many rich investors in India preferred direct equity (often via brokers or their own research) or real estate. But in recent years, HNIs are increasingly entrusting funds to structured portfolio services, reflecting a desire for expert management and diversification beyond plain-vanilla mutual funds.

Discretionary PMS AUM rose from ₹13 trillion in FY2019 to ₹31.8 trillion in FY2025, a 16.1% CAGR. This is impressive, considering this period includes the volatile pandemic years. Interestingly, the number of PMS clients grew at only 5.5% CAGR (from ~1.39 lakh to ~1.91 lakh investors), which implies that average ticket sizes have increased substantially – essentially, existing HNIs are allocating more money into PMS, and new PMS investors coming in are fairly wealthy.

Indeed, the average PMS account size is orders of magnitude larger than the average mutual fund folio. In FY2025, the average value per mutual fund folio was only around ₹30,000 (₹0.03 million), whereas the average ticket size in PMS runs in the crores of rupees (tens of millions). This dichotomy underscores that PMS is the domain of the affluent, but it’s a fast-growing one.

Why are HNIs flocking to PMS? A few reasons emerge:

Customization and Advisory: Unlike mutual funds, which are one-size-fits-all for a category, PMS offers tailored portfolios, often concentrated and aligned to an individual’s goals or risk profile. HNIs appreciate having a say or a bespoke strategy (e.g., a focus on a particular theme, or excluding certain sectors), managed by seasoned portfolio managers. This advisor-led allocation appeals to those who outgrow generic funds and want a high-touch service.

Higher Risk Appetite: HNIs often seek higher returns and are willing to take more concentrated bets. PMS strategies can take concentrated positions and are not bound by the strict diversification norms of mutual funds. Many PMS products have delivered market-beating returns by focusing on mid/small-caps or unique strategies, attracting HNI money that chases alpha beyond what mutual funds (designed for the masses) can reasonably target.

Regulatory and Market Evolution: SEBI’s regulatory tightening on mutual fund TER (fees) and standardization of categories made mutual funds more homogenous. PMS, being less regulated in product structure (though heavily regulated in operations and disclosure), became the avenue where innovation in strategy migrated. For instance, long-short strategies, thematic plays, or very concentrated holdings are more feasible in PMS. HNIs who wanted these sophisticated approaches moved money from their own trading accounts or from generic funds into PMS. The booming equity market also meant those who gained wealth were looking to deploy it in professionally managed ways.

It’s also worth noting that a significant chunk of PMS AUM in India includes institutions like the EPFO (Employees’ Provident Fund Organisation) allocating to equities via PMS managers. Some reports put total PMS AUM (including EPFO and other non-discretionary assets) at ~₹37 trillion by end-2024. Excluding the EPFO (which accounts for a large portion invested in index strategies), the “pure” HNI-driven PMS AUM was around ₹6.6 trillion by Dec 2024. This suggests that while the headline PMS figures are large, the retail/HNI discretionary part is a subset. Nonetheless, that subset is growing fast, and the number of wealthy individuals using PMS doubled in the last decade (from ~58k in 2014 to 1.5 lakh in 2024), mirroring the overall wealth creation in the economy.

The rise of PMS indicates greater financial sophistication at the top end of the market. Indian HNIs are gradually shifting from traditional avenues like ULIPs or endowment insurance plans (which were popular in the 2000s) and direct stock punts, to more structured vehicles. This is a positive for market transparency and governance, as PMS and AIFs (Alternative Investment Funds, like venture capital or hedge funds) bring more money into well-regulated, SEBI-supervised channels. It also complements the mutual fund growth: while the broad middle class goes into mutual funds via SIPs, the ultra-rich deploy capital via PMS and AIFs. Both trends point to the formalisation of investments across the spectrum of wealth. And as PMS performance and practices become more visible, they could eventually entice the upper-middle segment as well (for example, we already see new “tech-enabled” PMS platforms trying to lower ticket sizes and attract young rich professionals, indicating a trickle-down effect of these services).

In summary, the HNI segment in India is also moving away from purely physical assets or ad-hoc investing to formal financial products, mirroring what’s happening at the retail level. The era of the stock-tipping uncle handling a rich family’s portfolio is giving way to professional managers and systematic strategies. This bodes well for the efficiency and depth of Indian capital markets, as more money is managed by institutions that can deploy it in productive avenues (equity, debt, venture capital, etc.) rather than sitting idle or in gold/real estate.

Global Context: How India Stacks Up

As we’ve seen, India’s financialization of savings has made great strides, especially in the past 3–5 years. But how does India compare with other major economies in this regard? Global benchmarks put India’s position in perspective – highlighting both how far it has come and how far it can still go.

On retail participation metrics, India is still an under-penetrated market. We discussed demat account penetration (~14% of population).

By contrast, countries like the United States have a much higher share of the population in the stock market, though measuring exact participation is tricky (in the US, many invest via retirement plans and mutual funds rather than direct brokerage accounts). Surveys suggest roughly ~55% of American adults own stocks (directly or indirectly), often through 401(k) plans, mutual funds, or pensions. In India, that comparable figure (counting any financial asset like stocks, mutual funds, etc.) is in the teens.

China has seen a retail stock trading boom over the past two decades; with demat-like accounts at ~28% of their population, China is ahead of India but still not near Western levels. In Japan, despite a high demat account penetration (~30%), actual retail trading activity is somewhat subdued (cultural risk aversion and an aging population lead many Japanese to prefer bank deposits or postal savings over equity investing). The UK and Europe have high mutual fund and pension participation but relatively fewer individuals trade stocks directly (many leave it to institutional products).

Another global lens is household asset allocation. In countries like the US or UK, a much larger portion of household wealth is held in financial assets (equities, bonds, funds, pensions) versus physical assets. In the US, for instance, real estate (home equity) is a major component, but equities and investment funds form a huge share of household net worth. In India, by contrast, real estate and gold traditionally dominated. This is gradually changing. Urban, younger Indian households today allocate a higher share to financial assets than their parents did, but it will likely be a generation or more before India’s overall household asset mix resembles that of a developed country. The upside is that India can grow its financial markets significantly as this rebalancing happens.

It’s also instructive to consider the role of domestic investors in the stock market. In the US, domestic institutional investors (mutual funds, ETFs, pension funds) and retail investors own the majority of the stock market capitalization, with foreign investors owning a smaller share. In India historically, foreign investors (FPIs) owned a large chunk of the free-float market cap. That is now changing: domestic investors (retail + domestic institutions like mutual funds and insurance) have been steadily increasing their share of Indian equities. As of 2023, domestic institutions and retail together owned roughly similar if not greater share of the market as FPIs – a significant turnaround from, say, a decade ago when FPIs overwhelmingly dominated net flows. This means India’s markets are maturing, relying more on its own citizen investors, much like developed markets do. It also means market dynamics are changing – for example, retail investors often behave differently from FPIs (retail may buy dips that FPIs cause, etc.), which can reduce volatility and align market movements more with local sentiment than global risk factors.

China’s households also historically preferred physical assets (especially real estate). In the last decade, the Chinese government pushed to develop mutual funds and pensions, and there was a retail stock trading boom in 2014-2015. Yet, China’s AUM/GDP at ~23% is still higher than India’s 18%. This suggests India might follow a similar path – a rapid rise to say 20-30% as the middle class joins in – but beyond that, further growth needs deeper financial system infrastructure (like large pension funds, etc.). Japan has high per-capita wealth but a cautious investor class; still, its mutual fund AUM/GDP at ~43% is several times India’s. The UK at ~53% and USA at ~69% show what mature markets look like – although one should note the US number might exclude certain institutional assets; the US mutual fund industry is actually enormous (over $26 trillion in assets, which is closer to 125% of US GDP, per Federal Reserve data). The 69% figure likely refers to mutual funds excluding certain institutional holdings, aligning with retail-focused assets.

The key takeaway is India is in the early-to-middle innings of financialization. There is a long runway ahead. If India’s economy grows as projected (to $5 trillion and beyond), and if the cultural shift towards financial investing continues, we could see exponential growth in the number of investors and the volume of assets.

For instance, reaching even 30% AUM/GDP (from 18% now) in, say, a decade, would imply the mutual fund industry multiplying itself while GDP also increases – a powerful compounding effect for capital markets. Similarly, if even a quarter of India’s population eventually participates in equities (direct or via funds), that would be nearly 350 million investors – roughly triple the current count. Achieving these figures will depend on structural factors like financial literacy, regulatory support, and trust in markets, but they underscore the potential scale of India’s financialization.

Implications for Founders, Fintechs, and Market Participants

The transformation in household savings isn’t just a dry statistic – it carries far-reaching implications for various stakeholders in the economy:

Opportunities for Fintech & Startup Founders: The massive influx of retail investors has effectively created a new market of customers for financial services. Fintech startups are at the forefront of capturing this opportunity. Companies like Zerodha, Groww, Upstox, Paytm Money, and others leveraged the retail trading boom to amass millions of users, often by providing seamless digital experiences and low costs.

For example, by late 2024 the top five discount brokers (including these fintech platforms) accounted for 64.5% of all active clients on NSE – up from 62% a year prior, indicating rapid client acquisition by tech-driven players.

Founders in the fintech space can draw several lessons: user experience, low friction onboarding, and educational content are key to converting the huge population of savers into investors. The scope isn’t just in brokerage; adjacent opportunities abound – robo-advisory, goal-based investment apps, micro-investing platforms, online bond/debt investing portals, wealth management for the masses, and financial planning tools – all can ride the wave of greater financial engagement.

We are already seeing new startups offering features like fractional investing in US stocks, digital gold, or smallcases (curated stock baskets) to cater to the evolving preferences of retail investors. Furthermore, as more Indians seek financial advice, AI-powered advisory or hybrid advisory models could scale to serve millions at low cost.

In short, fintech founders are operating in perhaps the most exciting era of Indian retail finance, akin to the discount brokerage revolution in the US in the 1980s or the dot-com boom for online trading – except now aided by smartphones and UPI. The winners will be those who can acquire users sustainably (riding the current wave) and retain them through market cycles (perhaps via superior advisory or product diversification).

Implications for Early-Stage Investors and Startups: A deepened capital market is good news for the startup ecosystem in a couple of ways.

First, more household money in equities can translate to more eventual money in venture capital and startups. As individuals get comfortable with public markets and create wealth, a subset often looks for the next frontier: private markets. India is already seeing a rise in angel investors and micro-VCs, many of whom are professionals or entrepreneurs flush with gains from equity investments.

A cultural acceptance of equity risk is a necessary precondition for a thriving startup investment culture; the current trends are building that foundation. Second, a robust public market provides clearer exit pathways for venture-backed companies. The period 2020–2021 saw several high-profile tech IPOs in India (Zomato, Paytm, Nykaa, etc.), backed by significant retail interest. While some of those IPOs had mixed post-listing performance, the fact that Indian markets could absorb large new-economy IPOs is encouraging. As the retail investor base expands, the appetite for new issuances (including tech IPOs) should remain strong, giving VCs and founders confidence that they can list in India and get good valuations supported by domestic investors.

Moreover, M&A and secondary markets also get a boost when asset prices are high and capital is abundant – we’ve already seen established companies becoming acquirers of startups (often funded by their own high market valuations). Early-stage investors benefit from this dynamic through potentially higher exit multiples.

For Traditional Financial Institutions: Banks, brokerages, and asset management companies face the challenge of adapting to a more tech-savvy customer base. Incumbent banks, for example, are rolling out or enhancing investment platforms within their mobile banking apps to prevent customer attrition to dedicated fintech apps.

Asset management firms are witnessing direct-to-consumer fintech distribution (e.g., Zerodha’s Coin, Groww) gain ground over traditional distributor channels. This pushes them to innovate in product offerings (like smart-beta ETFs, international funds, etc.) and to engage investors with more transparency and digital tools (robo-advisory tie-ups, for instance).

The good news for these institutions is that the pie is growing – the overall AUM and equity participation are rising, so even if market share is fragmenting, the absolute volume of business is increasing. For example, brokerages are seeing record transaction volumes and exchange turnovers (India’s equity trading volumes, especially in derivatives, have hit all-time highs, partly due to retail activity).

Similarly, mutual funds are collecting record SIP inflows, providing steady fee income to AMCs. The flipside is increased competition: with low-cost fintech platforms in the fray, fees and commissions are under pressure. TERs of mutual funds have been cut by regulation and competition, brokerage charges have gone to zero for standard plans – all this benefits consumers but forces players to find new revenue models (value-added services, lending against securities, subscription fees for premium features, etc.).

Capital Markets and Exchanges: A larger domestic investor base is a boon for stock exchanges and capital market depth. The liquidity in mid- and small-cap stocks has improved in the last few years due to retail participation, reducing bid-ask spreads and making the market more efficient in those segments. Exchanges (NSE, BSE) gain from higher trading volumes (2023–2024 saw consistently high turnover, with F&O volumes skyrocketing).

However, more retail trading also means greater responsibility to prevent misconduct (e.g., pump-and-dump schemes targeting gullible investors on social media) and to ensure systems can handle surges (Indian exchanges had to manage record number of trades per second on volatile days, a good stress-test for infrastructure).

Regulators and exchanges have already taken steps like tighter surveillance on penny stocks, regulations on algorithmic trading APIs used by retail, and so on, to curb excesses. Investor protection initiatives – such as education campaigns, simplified complaint redressal mechanisms, and demat account nomination drives – have also intensified, recognizing that first-time investors need support and safeguards.

Macroeconomic Implications: From a macro perspective, the financialization of savings is generally positive. It means more savings are getting channeled into productive investments (via banks, bonds, equities) rather than sitting as gold or cash.

This can improve the allocation of capital in the economy, potentially lowering the cost of capital for businesses. For instance, the rise in mutual fund AUM provides a domestic pool of capital for both equity and debt financing of companies (AMFI data shows mutual funds’ holdings of corporate bonds and government securities have also increased, helping broaden the debt market).

A larger equity culture also allows companies to deleverage and raise equity capital more easily (we’ve seen many companies do QIPs or rights issues in 2020-21, which were absorbed well thanks to ample liquidity). Furthermore, a nation of investors contributes to a culture of ownership and financial literacy – people start paying more attention to economic policies, corporate governance (AGM participation by retail is rising), and even political decisions that impact markets.

This could, in the long run, lead to a more informed electorate that favors stable, growth-oriented economic policies (some cite the large investor class in the US as a force that advocates for market-friendly policies).

On the flip side, there’s the risk of market euphoria or bubbles when novice investors pile in – something policymakers will have to watch. But so far, Indian regulators have been proactive in tempering excesses (for example, curbing speculative margin trading, implementing risk management for brokers, etc.).

Financial Inclusion and Literacy: The trend also ties into the broader agenda of financial inclusion. India has made great strides in basic banking inclusion (hundreds of millions of Jan Dhan accounts opened). The natural progression is to move from just having a bank account to using that account for saving and investing. Fintechs are trying to bridge that gap by offering digital investment products to first-time earners in small towns.

The more people invest, the more they will demand financial knowledge – which in turn creates demand for investor education content, advisory services, and even courses.

We’re seeing a proliferation of financial influencers (FinTok, YouTube finance channels) and workshops catering to new investors. While not all information out there is quality-checked, over time the ecosystem is likely to mature, with perhaps certifications for advisors or verified content platforms. Startups that focus on financial literacy as a service could find a niche, possibly in partnership with schools, employers, or government programs. Already, some neo-banks and brokers have built learning modules and simulators to educate users within their apps.

In essence, the shift of household savings into financial assets is creating a virtuous cycle: it funds new enterprises, stabilizes markets, enriches households (who earn better returns than traditional instruments), and encourages even more participation. For entrepreneurs and investors, understanding this evolving landscape is key to strategizing products and investments.

A fintech founder might target the next 100 million investors with a vernacular app and small-ticket SIPs. An early-stage VC might anticipate that more liquidity and retail enthusiasm could mean certain consumer fintech or investment tech startups can scale faster now than five years ago.

In conclusion, India’s journey of financialising household savings is transformative for the economy. In a short span, Indian households have evolved from being primarily savers in physical assets or bank FDs, to investors in a gamut of financial instruments.

This change enhances capital availability for businesses, empowers individuals to beat inflation and build wealth, and gradually aligns India with global norms of investment-led growth. Overall great progress has been made, “but a long way to go”. For founders and investors reading this, the key takeaway is that the landscape is getting richer (both figuratively and literally). Loads of opportunities to build and make money here, riding this trend.

There will be more customers to serve in financial services, more capital to fund ventures, and more domestic firepower in capital markets.

At the same time, with great opportunity comes great responsibility – the onus is on all market participants to ensure this shift is sustainable by promoting transparency, literacy, and prudent practices. If done right, the financialization of India’s savings will be a cornerstone in the country’s climb to middle-income and eventually developed economy status, creating value for decades to come.

Disclaimer – The views presented here are my own and doesn’t reflect views of my employer in any way and it shouldn’t be construed as that in any way whatsoever.